This book contains the worst sentence I've come across by Agatha Christie:

"Anthony took a gingerly sip of coffee."

Something about its sheer wrongness captivates me. "Anthony gingerly took a sip of coffee" would be fine. "Anthony took a nervous sip of coffee" would also win. Instead we have this weird monstrosity - I have to admit, it fascinates me.

Why? This isn't me jumping on the "Agatha Christie can't write" bandwagon. Graeme Greene apparently sneered she employed the English of a schoolgirl - which misses the point. Agatha Christie is a brilliant writer. There are many, many other writers from the Golden Age of Crime who are now forgotten; barely readable then, utterly unreadable now.

If Agatha Christie merely constructed amazing plots thinly plastered over with simple words, then she wouldn't still enjoy her amazing success. A good writer has great characters and it is her characters that people still talk about - everyone knows Poirot and Marple.

Agatha Christie has a style - you've only got to look at the marvellous wrongness of The Big Four when one of her relatives rolled up his sleeves and pitched in, keen to prove that anyone can have a crack at writin' one of these crime thingies, to realise that only Agatha Christie can write Agatha Christie. The Big Four is all plot and no style (and what a plot - sinister Chinees, death rays and dastardly doubles. Blimey).

At the other extreme is Postern of Fate which is all style and no plot. But it's remarkably entertaining and a great read purely because of the style. People do read Agatha Christie because of the writing.

So why am I picking on this one sentence? Because it allows me to arbitrarily point, midway through her career and say "she's become uneditable". Just as people highlight the moment when Harry Potter went from books to tomes, this is the moment at which Agatha Christie editors started waving her works through regardless. Or perhaps it was because there was a war on.

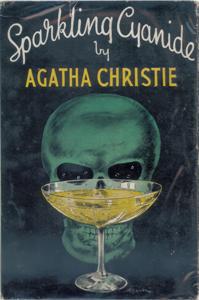

There certainly isn't a war on in Sparkling Cyanide. It's a curiously timeless, vaguely pre-War book in which the coffee is bad, but an heiress's only trouble is what to do with her money. There's perhaps a hint that the meagreness of rationing preyed on the author's mind - we get an unusually loving recitation of the fatal menu at the Luxembourg, conjured up with all the lavish attention employed for one of Lord Snooty's feasts.

The novelty in the book is that the central crime has already happened before page one. I read on, confidently expecting a flashback, but it never came. The crime is instead relived in moments, and then recreated with a fatal twist that takes you by surprise.

The victim - Rosemary - hovers over the book like a ghost, and we get a picture of her from the point of view of the suspects, several obsessed by her, but only one of them liking her. She deliberately never really appears - she is Christie's Rebecca.

The book is a character study - in some ways the actual crimes and investigation are an anticlimax to the people. For instance, the devious politician and his docile wife who, it transpires, is a much more complicated personality than anyone else even guesses at - Christie's masterstroke with poor Lady Alexander is that she reveals her brilliance to the reader, and then draws the curtain again, so we must read the second half of the book with everyone from her parents to casual acquaintances dismissing her as "mad" and "gothic". This leads to a remarkable scene where her parents, convinced of her guilt, confront each other:

"They looked at each other - so far divided that neither could see the other's point of view. So might Agamemnon and Clytemnestra have stared at each other with the word Iphigenia on their lips."

See? Marvellous stuff. The book is full of lovely bits of style, and Christie indulges herself shamelessly with a nutty spinster ("Twitterers can tell one a lot if one just lets them - twitter") as well as some spot-on observation:

"Iris's face adopted that same look of blank enquiry that her great-grandmother might have worn prior to saying a few minutes later "Oh Mr X, this is so sudden!"

Underneath all this razor sharp invention is a plot that almost... almost cheats. Christie takes you into the confidence of all of the suspects, while at the same time dragging a huge red herring across the trail. The reveal (when it comes) works, and works cleverly, but the reader is allowed the same kind of groan as when on the receiving end of a truly terrible pun.

Looking back you realise that all of the hints have been there, and everyone who should have been interviewed was, and all lines of enquiry were pursued... but... but... still. You've been well and truly had.

Her ingenious conclusion does even excuse the one wopping bit of racism in the book (we'll sadly wave through the other jarring references to Negro bands).

We meet again Colonel Race (who permeates Christie without ever really being more than a cameo), there is mention of Sergeant Battle, and there is even, quite surprisingly, a maid called Evans.