JAMES: We're starting at the beginning. And it's already archetypal Agatha Chrisite - Poirot investigates a locked-room mystery in a country house. But this book is about so much more than that.

JAMES: We're starting at the beginning. And it's already archetypal Agatha Chrisite - Poirot investigates a locked-room mystery in a country house. But this book is about so much more than that.For a start, it's a war novel - a First World War novel. And there aren't many of those. This genteel murder takes place while the guns go crump at The Front, which lends the book an odd air. Why should this single death matter when thousands are dying every day? And yet it is made to matter, due to Poirot's great humanity. While everyone else tuts about rationing, reads war poems, or decries the state of the gardens now that the servants are dead, it is Poirot who is the human centre.

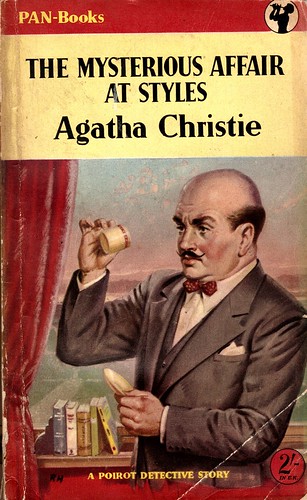

We first meet him as a refugee. He's a dispossesed pensioner, limping from a war wound. Once Poirot was the world's greatest detective, but he's clearly on his last legs here. Even living in poverty-stricken solitude, he's still a commanding presence. And yes, he's an ecentric, fussy oddity right from the start, with his enormous egg of a skull and his precise manners - and yet he's the one person who cares the most about the murder victim, and about ensuring a happy outcome for the rest of the family. He even refers to himself as "Papa Poirot", asking the strange ragbag of ciphers to confide in him.

Because, yes, the guest cast are a strangely lifeless bunch. There's two plucky gals, two poor gentlemen, a bounder and a foreign doctor. Plus a dippy maid and a no-nonsense housekeeper. It's a little hard to differentiate them at times. The victim's boon companion, Miss Howard, is all guts and thunder and enormous fun, and that's about it. Oddly, some of the cameos, such as the out-of-breath chemist or the excited housemaid come across more sharply than some of the suspects.

Much is made of the "unreliable narrator" in her later work, but Christie gets right down to it with Captain Hastings. In the beginning he appears to be the detective who "came across a man in Belgium once. A very famous detective. My system is based on his, though of course I have progressed rather further". We see Christie at her funniest as we gradually realise how inept Hastings is, deliberately unleashed on the household by Poirot as an enormous distraction.

This device is oddly similar to Christie's contemporary PG Wodehouse. While Poirot solves all problems and mends all broken hearts with the tact of Jeeves, Hastings is poor old Bertie Wooster, blundering about, making disastrous proposals of marriage, and coming up with harebrained scemes. Actually, look at Right Ho, Jeeves (1934) - it's practically the same book. Only with less murder and more newts.

If Hastings is an enormous red-herring, then so too is much of the book. Suspects are ruled out in quick succession, there's much business with various different bottles of poison, amateur dramatics, and even a whole plot about spies. What's so clever is that each red-herring is actually not the complete distraction it seems, building up to a brilliant denoument, which makes you think "oh, now, hang one a minute... that's not playing fair".

It's an unusual ending. It's suddenly a courtroom drama (which will crop up in stuff like Witness For The Prosecution), but it's handled with admirable skill by Christie - all bullying baristers and alarming retelling of evidence in a suddenly damning light. Will the case end in court, you start to think? Oddly, this is a formula used in every Perry Mason novel, but here it's just a fourth-act distraction before Poirot slaps his forehead and summons everyone into a drawing room for the "You may be wondering why I called you here today" denoument that we know, love and expect.

Finally, a lot of noise is made about Chrisite the racist/ anti-semite, which I hope to find out more about as we go on. But here, oddly, the one Jewish character is treated with surprising sympathy, even with admiration by Poirot. I'm prepared to be wrong (and I'm sure The Book With The N-Word will get me), but I'm going to advance the theory that while Christie may make the odd incidentally insensitive comment, her overall view of foreigners is sympathetic. My big reason for this is amazing Poirot. He's the constant butt of snide, sour racial intolerance, but he triumphs over it. If anything, Christie's approach seems to be that the British are simple-minded buffoons, all manners and no thought. Hastings and his friend Cavendish are true members of the Drones Club - frequently lost for words, emotionally stunted, and incapable of independent thought. It is this staid quality that nearly lets the murderer get away with it - and proves that England really does need outside help. Even if from a damned Belgie like Poirot.

With hindsight, it's hard not to draw parallels here with the senseless slaughter going on on the continent. The survivors of that Great War will provide much of the guest cast for the rest of Christie's oeuvre. And frequently, they're not valiant heroes, but blundering old salts and stuffy sahibs. Which makes you wonder what point's being drawn there too.

KATE: This first Christie novel is both completely typical (country house murder, limited cast of suspects, collection of slightly stock characters from faithful servant to winsome young love interest….) and quite atypical in its use of courtroom drama and the legal technicality the ending hinges on.

KATE: This first Christie novel is both completely typical (country house murder, limited cast of suspects, collection of slightly stock characters from faithful servant to winsome young love interest….) and quite atypical in its use of courtroom drama and the legal technicality the ending hinges on.Outside ‘Witness for the Prosecution’, legal procedures rarely impinge on Poirot’s deductive process. Not only do we rarely see the inside of a courtroom, but in many of the novels, Japp and his slow-witted colleagues never get as far as an arrest. As the series develops, Christie sometimes goes out of her way to exclude the police from the action, setting plots on islands, in snow-bound trains and at remote archaelogical digs where Poirot is on his own to solve the case without official support or forensic evidence.

While I’d agree that Christie’s treatment of Poirot is sympathetic, especially in contrast to the wooden English gentry who surround him, he is always an isolated figure. Ever the foreigner who sticks out like a sore thumb in this green and pleasant England, not only is he the stranger who intrudes on family crises, but a solo private detective who is unable to confide fully in sidekick Hastings, who would inevitably give the game away. He appears at his most pitiful and most foreign in ‘Mysterious Affair at Styles’, a refugee, living on charity, who couldn’t be more different from his benefactors the Inglethorpes. As Christie’s portrayal of Poirot develops, he starts to use that foreignness strategically, knowing that the average Englishman will assume anyone with a foreign accent must be a halfwit.

I think you’re bang on in comparing this to Wodehouse; in much the same way as he presents light, diverting tales of upper-class life, Christie’s writing intellectual jigsaw puzzles that barely graze the surface of real life. Sympathy for the victim is almost beside the point – their death isn’t a human tragedy, just the jumping-off point for the puzzle that has to be solved. In a stoicism perhaps borrowed from the bloody front of the First World War, the victim’s relatives and friends never seem so much devastated by death as inconvenienced by it. Unlike most contemporary crime, it’s not unusual for Christie’s victims to be the least likeable characters in the story, for whom you’d struggle to feel much regret.

Murder in the house means delaying dinner and the delicate social problem of how to feed visiting policemen (usually with beer and sandwiches in the butler’s pantry). Even Poirot “does not approve of murder” and, habitually neat as he is, seems driven to tidy up the mess more than to punish the killer or avenge the dead. Littered with comic relief (mainly provided by the blundering Hastings), these are stories intended to divert the reader and impress them with Christie’s cleverness, not set them musing on the human condition.

Speaking of victims, what did you think of Mrs Inglethorpe – innocent victim, or dominating matriach who brought it on herself?

JAMES: Ooh, she's curious, isn't she? She's a figure of great charity, but she's also shown as vain, domineering and capricious, who loves using her money as power over those close to her.

JAMES: Ooh, she's curious, isn't she? She's a figure of great charity, but she's also shown as vain, domineering and capricious, who loves using her money as power over those close to her.NEXT: Poirot in a valiant thriller, The Big Four

I happen to be in the middle of re-reading (for about the 3oth time) a bunch of Agatha Christies, so I'm very interested in your thoughts as you go along. I agree generally with what you've both said; it's actually remarkable how much of the pattern for the rest of her books is already present in this novel. Re: the lack of great grief about the victims... I've noticed that this is a feature of many detective novels, both classic and modern; I think part of it is the sheer impracticality of writing an interesting puzzle and unraveling it if the main characters are truly prostrate with grief, or traumatised, or any of the things that they ought to be (and would be in real life). And part of Christie's strategy, often, is to make the victim not terribly sympathetic, but instead to focus our sympathy on a potential suspect or two, so that the tension comes from our concern that someone we like may be unjustly accused. Which is echoed in Poirot's attitude (made explicit fairly often later, as in "Cards on the Table" that I've just read) that his concern is not so much for the victim, but for the murderer; that someone who takes the step of deciding whether another person should live or die "Usurps the function of le bon Dieu" and will grow accustomed to it, and be dangerous.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, sorry for maundering on, I look forward to reading your thoughts on the rest of the oeuvre!