I've never liked the "N-word". It's one of those words that manages to sound offensive and derogatory, in the same way as "Faggot" or any of those short and magnificently abusive Anglo-Saxon terms that just slip out whenever I try and use the Northern Line. It's a horrible, nasty word, and one that is, these days, thankfully repugnant. Like parquet flooring, it is being usefully reclaimed, but it remains pretty much unusable and unsayable unless in very careful contexts.

It is scattered through the first version of Agatha Christie's most infamously titled book like bones in a kipper. The expurgated text is a far easier read nowadays, and one in the eye for the "political correctness gone mad" brigade. I've just finished reading the original version, and it's a mildly queasy journey. The sheer outdated proliferation of the word is simply a distraction from a brilliantly good book. If the book wasn't so good, I don't think so much of a fuss would have been made about the troublesome title.

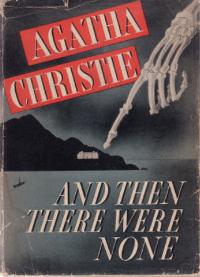

One thing that surprised me was discovering that the book was known as "Ten Little N-s" in England up until 1979. Really? Even more alarming was looking at the cover of my 1979 Fontana edition:

This neatly knocks on the head the BNP's odious argument that the Golliwog has no racial connotation and is simply a figure of fun like a teddy bear. Yeah right. It also, if you look at the lizard's face, contains a pretty massive clue to the murderer. So, it's doubly offensive.

But how sensitive should we be about this? In Christie's defence, she's certainly not the only author of the period to use the term, and she uses it with all the thoughtless abandon of someone with no offensive intent. This is not a book aimed at inciting racial hatred - the use of the N-word is such an incidental detail that it's almost Christie's biggest ever red-herring - and the success with which the text has been stripped of it proves how inconsequential it was to the narrative in the first place. Indeed, American pretty much immediately insisted on calling the book "And Then There Were None" - this book isn't known over there under the original title, which made for quiet a surprising recent protet in the US when a local NAACP president tried to block a High School production of the play And Then There Were None - on the grounds that it was based on a book which had once had a different title In Another Country. Which seemed a bit surprising - but then one has to, just as with Christie, be aware of the context. A lot of the reporting of this case appears to be from what you might call the political right. As I said - context it everything.

For instance, And Then There Were None does contain one really racially repugnant character - a horrible Jewish man, who is mocked and villified. Which is particularly unpleasant since this is 1939. You can mount a defence that we only really see Mr Isaac Morris from one character's viewpoint, and he's not necessarily sympathetic... but still, it's unfortunately tactless to say the least. Which is about the worst you can see about this book.

With that lengthy preamble to one side... what about the book? Well, it's utterly brilliant. It's a great concept - 10 strangers all at the mercy of a mysterious nemesis. It's easy to forget that it's not until late on that you realise the murderer is amongst them... or are they?

This is a game of psychological torture played out with the usual Christie suspects (Dashing Young Man, Military Man, Old Maid, Colonial Adventurer, Noble Mouse, Humble Retainer etc...) the exception being that They're All Guilty.

Freed from having to have a proper investigation, or even really a detective, Christie runs wildly experimental. We really see inside everyone's minds - these are complicated people, for once deceiving themselves rather than Hercule Poirot. There are even a few remarkable scenes where Christie treats us to everyone's inner thoughts - including the murderer's. It's really thunderingly good at what it does - it's about suspense and justice and victims and innocence.

It's curious - these people are all scoundrels, but you do find yourself rooting for some of them. Christie is so good at drawing these types of people that it's hard to hate all of them. She even take great delight at building up the first victim as a shining god among men, a truly handsome brute - and then swiftly polishing him off.

The rhyme works here more even successfully than in A Pocket Full Of Rye - it's more than just a narrative frame, it's almost a narrator, taunting and warning the cast as events press remorselessly on to their grim conclusion.

Interestingly the play version has a different ending - and, as this is the basis of the film, it is quite remarkable when reading the book to realise that events are taking a very different turn indeed.

Next: Festive fury in Hercule Poirot's Christmas

Racism was never a problem for Christie. If she stands condemned of anything it is snobbery and elitism

ReplyDelete